§ 5.4 Surrogacy Laws in the United States

The law regarding surrogacy is unsettled, and the practice remains largely unregulated. Many states are hesitant to enact legislation because given the advances in reproductive science, there will always be a factual exception to the rule, making it more appropriate for the courts to address each scenario on a case-by-case basis. Surrogacy is also a controversial subject in which many politicians are reluctant to become involved.

Many states have no controlling decisional law, but many states regulate surrogacy by statute. Historically, courts decided similar situations differently, and each state initially carved out its own way of dealing with contested surrogacy and parentage disputes. Historically, the courts have employed three tests to determine legal parentage: (1) intent of the parties; (2) genetic relatedness of the parties; and (3) giving birth.26 Each test provides different results. The trend, as reflected in court decisions and recently-implemented statutes, is toward honoring the intent of the parties with regard to parentage when they entered into an assisted reproduction arrangement.27 Other factors include whether the surrogate is genetically related to the child, whether the surrogate is compensated beyond ordinary and reasonable expenses, the age and reproductive history of the surrogate, and the marital status and sexual orientation of the intended parents.

Even in jurisdictions where surrogacy agreements are unenforceable, intended parents have had success in getting their names listed as parents on their children's birth certificates where the carrier is in agreement with the requested relief. In addition, married intended parents are now better protected following the 2015 Obergefell v. Hodges decision that allowed same-sex couples to marry across the country, which marital status expands the presumption of parentage that attaches to any child born to a married couple.28

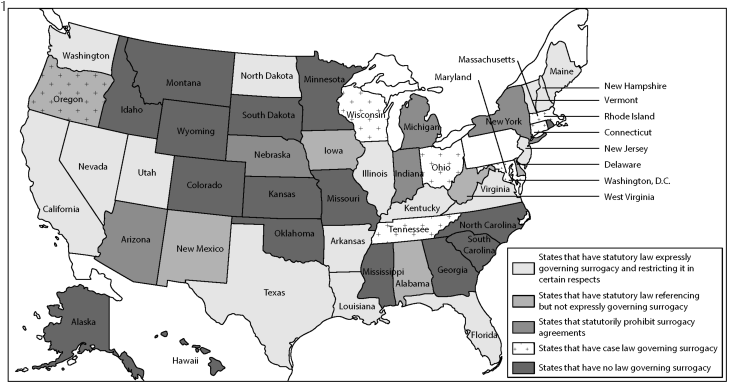

State29 surrogacy laws can be generally categorized as follows:

1. States that have statutory law expressly governing surrogacy and restricting it in certain respects: Arkansas, California, Florida, Illinois, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Jersey, North Dakota, Texas, Utah, Vermont, Virginia, Washington, and Washington, DC

2. States that have statutory law referencing but not expressly governing surrogacy: Alabama, Delaware, Iowa, Oregon, New Mexico, and West Virginia

3. States that statutorily prohibit surrogacy agreements: Arizona, Indiana, Michigan, New York, and Nebraska30

4. States that have case law governing surrogacy: Connecticut, Maryland, Massachusetts, Ohio, Oregon, Tennessee, and Wisconsin31

5. States that have no law governing surrogacy: Alaska, Colorado, Georgia, Hawaii, Idaho, Kansas, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, South Carolina, South Dakota, and Wyoming32

Given the variety of statutory and decisional law, it is important that parties to surrogacy arrangements obtain independent qualified legal counsel and memorialize their intent in a contract. In the event of a custody, visitation, or child support dispute following a surrogacy arrangement, ideally the parties will have entered into a contract that will provide a framework as to what the parties intended when they entered into their agreement, which is helpful from a legal perspective even if some of the contract provisions are ultimately unenforceable.33

Note: The law of the various states in the following list is accurate as of the end of May, 2018 when this book went to publication. Since the law in this area is undergoing frequent changes and development, practitioners should carefully consult the statutory and decisional law in the applicable jurisdiction to ensure that these descriptions are still current and accurate.34

Alabama

Alabama has an exhaustive statute criminalizing payment to encourage or facilitate adoption.35 However, the statute specifically exempts payments to surrogates.36 Presumably, then, a compensated surrogacy arrangement is lawful in Alabama. There does, however, seem to be an underlying intention in the statute to prohibit financial inducements to encourage adoption. As a result, parties should be mindful that payment to a surrogate, if substantial, could be construed as an attempt to induce her to give up any resulting child for adoption, subjecting the intended parents to potential criminal liability.

There is no known case law in Alabama addressing surrogacy. The US Supreme Court, however, did become involved in a same-sex parentage dispute in Alabama. The Supreme Court held that Alabama was required to give full faith and credit to a Georgia parentage order in a lesbian adoption case. In V.L. v. E.L., a same sex couple separated in Alabama and the biological mother tried to deny the nonbiological mother parentage rights. The Alabama Supreme Court did not give full faith and credit to the Georgia parentage order granting both women parental rights, which was reversed by the US Supreme Court.37

Alaska

There are no statutes or case law addressing surrogacy in Alaska.

Arizona

Arizona bans surrogacy contracts as contrary to public policy regardless of whether the woman carrying the baby is compensated.38 Any child born to a surrogate mother in Arizona is the legal child of the surrogate.39 If the surrogate is married, there is a rebuttable presumption that her husband is the legal father of the child.40 The statute explicitly prohibits both traditional and gestational surrogate parenting contracts.41 Presumably, if parties enter into a surrogate parenting agreement anyway in Arizona, the surrogate, whether acting as a traditional or gestational surrogate, would have to surrender any resulting child for adoption upon its birth for the benefit of the intended parents, in order to effectuate the intent of the parties.42 If the surrogate reneged on the agreement, however, the intended parents would have no recourse, as Arizona law declares surrogate mothers legal mothers and entitles them to custody.43

Arizona's statute was fashioned after the Michigan statute and was intended to prohibit surrogate parenting contracts altogether. However, in Soos v. Superior Court of the State of Arizona,44 the court declared the statute unconstitutional based on equal protection grounds. In that case, a married couple contracted with a gestational surrogate to carry the couple's embryos to term.45 Eggs were removed from the intended mother and fertilized in vitro with the father's sperm. The gestational surrogate became pregnant with triplets. During the pregnancy, the intended mother filed for divorce and requested custody of the triplets. The father responded, claiming that under Arizona law, he was the legal father and the surrogate was the legal mother of the triplets, negating the intended mother's standing to seek custody.46 An order was entered declaring the father the natural father of the triplets and awarding him custody. The intended mother responded by attacking the constitutional validity of the Arizona law declaring the surrogate the legal mother.

In Soos, the statute was held unconstitutional on equal protection grounds. The statute failed under the strict scrutiny equal protection analysis, a level of scrutiny applied because the case involved a fundamental right: It afforded a man the right to rebut the presumption of legal paternity by proving fatherhood but did not afford the same opportunity for a woman.47 Therefore, the intended mother in this case was denied the opportunity to prove her maternity. The statute violated the Equal Protection Clause because of this dissimilar treatment. Thus, under certain situations, an intended parent may be able to establish parentage even if he or she does not explicitly qualify under the statute.

Notwithstanding the Soos decision, the statute prohibiting surrogate parenting agreements continues to exist in Arizona. The decision in Soos merely stands for the proposition that the statute is unconstitutional to the extent that it provides men and not women the opportunity to rebut the presumption of paternity/maternity. The court explicitly stated it was not ruling on the question of the competing rights of biological and surrogate mothers. The case did not deal with the enforcement of a surrogacy contract or with a surrogate who reneged and wanted to keep the child. Rather, Soos addressed the constitutionality of the statute as it related to a custody battle between two biological parents.

Arkansas

The Arkansas statute carves out an exception for surrogates to its rule that a child born by means of artificial insemination to a woman who is married at the time of birth is the child of the woman and her husband.48 This makes Arkansas a surrogacy-friendly state, because it recognizes the reality of the situation rather than basing its laws on biology or gestation alone. A child born by means of artificial insemination to a woman who is not a surrogate and is unmarried is considered her legal child only.49 Arkansas raises a presumption, however, that a child born to a surrogate is the child of the intended parents and not the surrogate.50 If the child is born to a surrogate, whether she is married or not, the child is considered that of the biological father and the intended mother, if the biological father is married.51 In such cases, the intended mother is the biological father's wife. In the event that the biological father is single, however, a child born to a surrogate is the child of the biological father only.52 The statute also addresses situations in which a surrogate is inseminated with sperm of an anonymous donor; in such circumstances, the child is the legal child of the intended mother only.53 While those provisions honor the intent of the surrogate not to be considered any resulting child's legal parent, they simultaneously leave the child with only one legal...