CHAPTER 10 VOTER ID AS A FORM OF VOTER SUPPRESSION

NICOLE AUSTIN.-HILLERY

Sometime between 2010 and 2011, voting, as we knew it, changed. Prior to that, for most Americans, voting consisted of a few basic steps: register to vote, show up at an assigned polling place on Election Day, state your name, and cast your vote. With a few nuanced differences, such as casting an absentee ballot or participating in early voting, this was the standard voting protocol for the average American. Before 2010, Americans were not, as a rule, required to show any form of identification prior to casting a ballot.1 However, between 2010 and 2011, that all began to change.

In 2008, the Supreme Court ruled, in Crawford v. Marion County, that to prevent voter fraud the State of Indiana could require a potential voter to identify himself or herself by presenting a government-issued photo ID before he or she was allowed to cast a ballot. 2 The court "rejected the idea that a burden was placed on voters who needed to gather documents to get a free photo ID."3

The Crawford decision opened the floodgates to what would become a wave of efforts by more than 30 states to require potential voters to present some form of photo identification to cast a ballot.4 This was a momentous change.

Proponents of the new voter identification requirements argued that they were necessary to prevent voter fraud. Opponents argued that such requirements were unnecessary and had the effect—intended or not—of making it more difficult for African-Americans and other groups to vote.5

The United States has a long history of expanding access to the ballot,6 but the advent of laws requiring photo identification at the polls goes against that history. Despite what proponents of these new laws maintain—that they prevent voter fraud and strengthen the integrity of the voting process7—the experiences of voters show that these laws have done little more than suppress the vote.

I. How Did It All Begin?

States have attempted to require potential voters to show some form of identification before casting a ballot since at least1950,8 when South Carolina became the first state to require potential voters to show some kind of identifying document at the polls.9 South Carolina did not require voters to have a photo ID, but a potential voter was required to show a document bearing his or her name.10

It would be another 20 years before other states would join South Carolina in requiring some form of identification at the polls. In 1970, Hawaii implemented a voter ID requirement, followed by Texas in 1971 and Alaska in 1980.11The type of identification required by each state varied in form and kind—some states required photo identification while others simply required any form of documentation identifying the voter, whether or not it contained a photo.12Unlike many of the newer identification provisions of the 2000's, these earlier state laws allowed, in certain circumstances, voters to cast a regular ballot, rather than a provisional one, even when they did not have the required form of identification.13

Voter identification requirements began to gain momentum after the unprecedented chaos of the 2000 presidential election between George W. Bush and Al Gore. That election, which devolved into examinations of "hanging chads" and took a Supreme Court decision to determine the winner, badly shook the nation's confidence in the integrity of its federal election system.

The system was subject to intense scrutiny. In 2005, the bipartisan Commission on Federal Election Reform (also known as the Carter-Baker Commission) recommended the imposition of a voter identification requirement at the polls, along with other changes, to address waning public confidence.14 The Commission found that many of the problems that existed in 2000 remained and additional changes, such as voter identification, were warranted.15 The Commission recommended that each state provide registered voters with a free identification card.16

After the Crawford decision. Indiana implemented its strict voter ID scheme. Georgia soon followed suit.17 Both states required photo identification at the polling place and without it, voters were only allowed to cast a provisional ballot, which would only then be counted if the voter went to an elections office within a designated timeframe and showed the required identification.18

Things only worsened after Indiana and Georgiaenacted their voter identification schemes. In 2011, the Brennan Center for Justice undertook a comprehensive examination of the national landscape to gauge the impact of these new requirements. The report analyzed 19 laws and 2 executive orders, issued in 14 states, to measure their impact on voters.19 The report focused on an array of voting law changes that states had implemented or were attempting to implement, ranging from the shortening or elimination of early-voting days to changes in registration requirements. The report found that many states were requiring not just identification, but photo identification at the polls.20 The report estimated that 5 million voters could be affected by all of the voting changes that states were attempting to implement before the 2012 election.21

At least thirty-four states introduced legislation that would require voters to show photo identification in order to vote. Photo ID bills were signed into law in seven states: Alabama, Kansas, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and Wisconsin (though not all were slated to go into effect prior to the 2012 national election). By contrast, before the 2011 legislative session, only two states had ever imposed strict photo ID requirements. The number of states with laws requiring voters to show government-issued photo identification has quadrupled in 2011. To put this into context, 11 percent of American citizens do not possess a government issued photo ID; that is over 21 million citizens.22

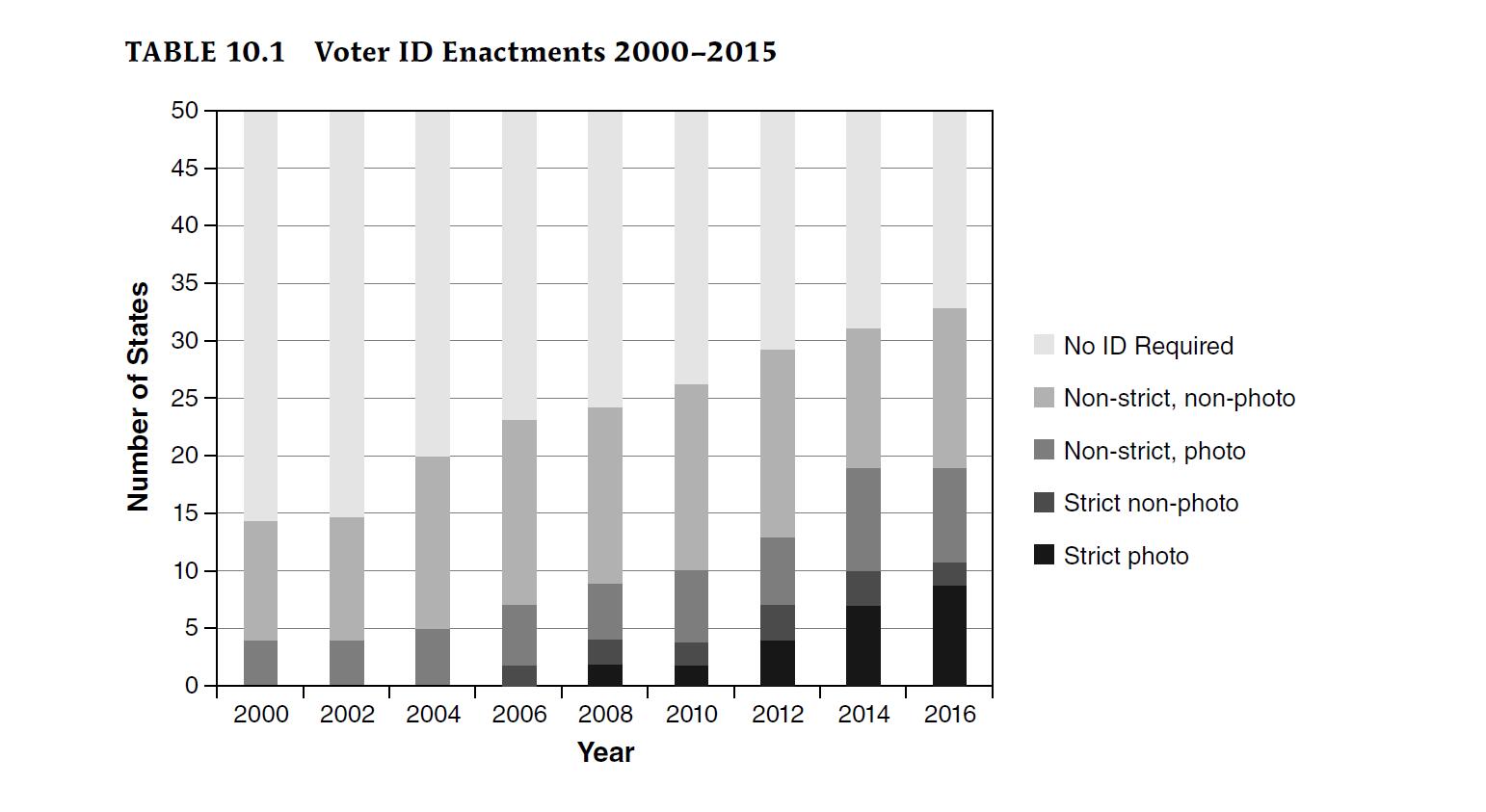

From 2011 through 2013, the pace of states adopting or proposing to adopt restrictive photo ID requirements quickened.23 States that never had ID requirements on the books continued to adopt them, and states that had less-restrictive requirements adopted stricter ones.24 Table 10.1 illustrates the number of voter ID laws enacted from 2000 to 2015.25

The impact of voter ID laws falls most heavily on young, minority, and low-income voters, as well as on voters with disabilities.26 Voter identification laws that disproportionately affect these groups are extremely problematic.

II. The Real Effects of Voter ID Requirements

Proponents of voter identification laws argue that these laws are intended to ensure that a registered voter is who he or she says he or she is and not an impersonator, and thus are meant to eliminate in-person voter fraud.27

TABLE 10.1 Voter ID Enactments 2000-2015

There are several problems with that argument. First, the fact that it is a felony for any individual to commit in-person voter impersonation,28 coupled with the fact that there is little, if anything, to be gained from one individual impersonating another person simply to cast one ballot, since one vote rarely swings an election from one candidate to another, means that such fraud should be highly unlikely.

In fact, such fraud is quite rare. A 2007 New York Times analysis identified just 120 cases filed by the Justice Department over five years—an average of only 24 cases a year. The Times' analysis found that many of these cases stemmed from purely administrative errors, such as mistakenly filed registration forms or misunderstandings over voter eligibility, and those 120 cases only resulted in 86 convictions.29 According to Richard Hasen, an election law specialist, when evidence of election fraud does exist, it is usually with respect to absentee ballots or election officials taking steps to change election results—the very types of fraud that photo identification requirements cannot prevent.30

Second, the fact that proponents have not focused their efforts on the most vulnerable parts of the election system, such as absentee voting, but have myopically focused their attention on in-person voter fraud, calls into question whether proponents are actually interested in protecting the integrity of the vote, or if voter identification requirements serve another purpose.

There are also issues with the way that voter identification laws have been implemented. Such laws typically delineate the types and forms of identification that are "acceptable," and the acceptable forms of identification tend to be the types that are more likely to be held by middle-class whites and less apt to be held by minorities, the elderly, and the young, groups that tend to favor Democratic candidates.31

Obtaining acceptable identification for any person can be costly and burdensome, but this is especially true for minorities, the elderly, and young people.32Even in states where acceptable forms of voter identification are purportedly free, the underlying documents required to obtain the free identification can be cost-prohibitive for individuals in these groups,33 and it is often difficult for members of these groups to travel to locations where free forms of identification are even available.34

How these voter identification laws will affect future voter participation and the outcome of future elections is of course, at this point, mostly conjecture. The 2016 elections will be the first time that many of the strict photo identification requirements will go into effect.35

Since the 2010 election, 21 states have enacted laws that make it harder to vote—ranging from photo ID requirements, to early voting cutbacks, to registration restrictions—and 16 states: Alabama, Georgia, Indiana, Kansas, Mississippi, Nebraska, New Hampshire, North Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, and Wisconsin, will have such laws in effect for the first time in a presidential election in 2016.36

...