By Lydia Robins Hendrix and Nekki Shutt

Law Alone Cannot Make Men See Right

On June 11,1963, John F. Kennedy addressed the nation on the "moral crisis" of racism, then culminating in acts of violence throughout the country. [1] That day, the National Guard had escorted two Black students onto campus at the University of Alabama in an effort to carry out a federal court order to admit Vivian Malone and James Hood: Governor George C. Wallace fought vigorously to block their attendance.[2] Just a month prior, members of the Ku Klux Klan had bombed Martin Luther King Jr.'s brother's parsonage, as well as the Gaston Motel, where civil rights leaders frequently lodged in Birmingham.[3] Acknowledging that these highly visible acts of violence were flashpoints in a larger crisis of inequality pervading the nation, Kennedy announced his intent to introduce what would become the Civil Rights Act of 1964 to the U.S. Congress the following week.[4] In that speech, Kennedy cautioned that "law alone cannot make men see right," acknowledging the need for nationwide legislation to "move this problem from the streets to the courts" while also imploring every citizen to take up their obligation to make racial equality a reality through their daily lives.[5] On June 19,1963, President Kennedy submitted his proposed civil rights bill to Congress.[6]

Off its Backside and onto Its Legs

Six months later, on November 22,1964, John F. Kennedy was assassinated.[7] Immediately upon assuming office of the presidency, Lyndon B. Johnson swore he would carry out Kennedy's dream for a civil rights bill.[8] The night of Kennedy's assassination, Johnson told an advisor that the bill would be his "first priority," promising to "get civil rights off its backside in the Congress and give it legs.[9] On November 25, Johnson gave a speech to a joint session of Congress, urging lawmakers to honor Kennedy by passing the civil rights bill.[10]

Johnson had his work cut out for him to get the bill onto its proverbial legs. The bill had been referred to the Rules Committee on November 20,1963, just before Kennedy's assassination.[11] There, Representative Howard W. Smith (D-VA)—a segregationist staunchly opposed to civil rights—refused to allow H.R. 7152 out of committee and onto the floor for debate in the House.[12] American citizens, however, had embraced Kennedy's vision for a civil rights bill, and Smith eventually conceded to public pressure to vote the bill out of committee on January 30,1964.[13] During the floor debate and just two days before the House vote on the bill, Representative Smith proposed an amendment to add "sex" to the list of protected classes to the bill—at that time expanded from race to include color, religion, and national origin.[14] Many have theorized that Smith inserted the language in order to derail the bill—having vehemently opposed to the bill at the outset—but Smith was allegedly sincere in the addition.[15] Finally, the bill passed the House on February 10 by a 290-130 vote.[16] That version of the bill—now gaining momentum—was far more robust than even Kennedy had envisioned. Relevant here, that bill included Title VII, the Equal Employment Opportunity provision of the bill.[17]

The bill may have had legs once it emerged from the House, but it faced an uphill climb in the Senate. There, three factions emerged: a bi-partisan group of pro-civil rights members; the Southern Democrats, led by Richard Russell from Georgia and joined by Republicans John Tower (TX) and Barry Goldwater (AZ); and moderate Republicans.[18] Inevitably, opponents of the civil rights bill initiated a filibuster.[19] Historically, filibusters had been effectively deployed to kill civil rights bills.[20]

Opponents of H.R. 7152, led by Senator Russell, started the filibuster in March 1964.[21] It lasted a record sixty days.[22] During that time, Johnson's advocates in the Senate prepared to actively debate the opponents of the bill, and rotating teams of the bill's proponents were to be available to arrive at the Senate chamber at a moments' notice.[23] The filibuster included a live televised debate between Democratic Senator Hubert Humphrey (MN), Johnson's floor manager, and then-Democratic Senator Strom Thurmond, who strongly opposed the bill.[24] Finally, on June 10,1964, Senator Everett Dirksen of Illinois gave a speech on the floor, remarking, "Stronger than all the armies is an idea whose time has come."[25] The time had, indeed come, and that day 71 senators voted to end the filibuster.[26] On June 19,1964, the Senate passed its version of the bill, and on July 2,1964, the House approved the final version—now formally the Civil Rights Act of 1964—by a 290-130 vote.[27]

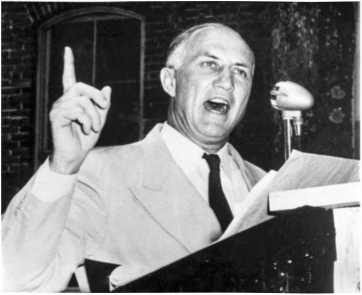

Strom Thurmond, U.S. Senator from South Carolina, led the longest filibuster in history (24 hours and 18 minutes), objecting to the 1957 Civil Rights Act. He also led the filibuster of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

A Purpose Not to Divide, but to End Divisions

Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 the night that Congress formally passed the bill as Pub. Law. 88-352 (1965),[28] Just before signing, Johnson addressed the nation.[29] Johnson's speech echoed the themes of Kennedy's address the year prior, calling for Americans to individually and universally take up the task of promoting justice and equality.[30] He said to the nation:

We must not approach the observance and enforcement of this law in a vengeful spirit. Its purpose is not to punish. Its purpose is not to divide, but to end divisions—divisions which have all lasted too long. Its purpose is national, not regional. Its purpose is to promise a more abiding commitment to freedom, a more constant pursuit of justice, and a deeper respect for human dignity.[31]

To that end, Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 seeks to ensure dignity of each employee in the workplace, prohibiting discrimination by employers on the basis of race, color, religion, national origin, and sex.[32] Its operative language states that it "is unlawful for an employer to fail or refuse to hire or to discharge any individual, or otherwise to discriminate against any individual with respect to his compensation, terms, conditions, or privileges of employment because of such individual's race, color, religion, sex, or national origin."[33] It applies to employers with at least 15 employees.[34]

In practice, Title VII has three major frameworks for discrimination cases, prohibiting conduct where an employee who is a member of a protected class experiences disparate treatment—in other words, intentional discrimination— resulting in an adverse employment action,[35] employer conduct that is facially neutral but has a disparate impact on a protected class,[36] and conduct that creates a hostile work environment.[37] The law also provides for relief where an employer retaliates against an employee for complaining of conduct prohibited by Title VII, and where an employer fails to accommodate an employee's religious belief or conditions related to pregnancy or childbirth.[38]

Major Developments in the Last 60 Years

Over the last 60 years, Title VII has transformed substantially, with several of the most robust developments taking place in the last decade.

A. Enforcement Powers of the EEOC

Title VII established a federal agency to enforce the statute, and on July 2,1965, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission ("EEOC") began its operations.[39] The EEOC is a bipartisan commission made up of five Commissioners appointed by the President and confirmed by the Senate.[40] Initially, the EEOC had no power to bring suits of its own, but had the power to file amicus briefs in private suits and could make recommendations to the Department of Justice.[41] In 1972, however, Congress amended Title VH to grant the EEOC litigation authority: finally, if the EEOC could not secure an acceptable conciliation agreement between an employer and employee, it could then institute suit against the employer.[42]

B. Expansion of Title Vil's Protections for Sex-Based Discrimination

As evinced by both Kennedy and Johnson's speeches at the outset of their efforts to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1964, elimination of racial discrimination was the primary impetus for the Act. Because protections on the basis of "sex" were added at the last minute to Title VII, there were no congressional hearings or a definition in the bill facilitate interpretation of the meaning of "because of sex."[43] As a result, the interpretation has developed over the years largely through judicial findings.[44] Where Congress found judicial interpretation of the Act to be flawed, it has refined Title VII over the years to expand the meaning of "because of sex" to pregnancy discrimination and to instances where an employer may have mixed motives when it discriminated against a worker at least partly on the basis of sex. [45] Some major developments to Title Vil's sex-related protections include:

• Price Waterhouse v. Hopkins, 490 U.S. 228 (1989), where the Supreme Court held that an employer could not escape liability where the employer had some permissible motivation, in part, when taking an adverse employment action against an employee.[46]

• Oncale v Sundowner...