October 2025

Alexandria Snyders Dykeman and Suzanne Harrington-Steppen, Esq.

Alexandria Snyders Dykeman, RWU School of Law Student 2026

Suzanne Harrington-Steppen, Esq. RWU School of Law Clinical Professor of Law

"Joseph Gelletich's life began to unravel in September of 2018,16 days after he missed a rent payment."[1] At age fifty-nine, Gelletich was living in an apartment that he planned to die in.[2] It was where he had lived with his boyfriend before he passed and where he began taking care of his mother.[3] After missing one month's rent, his property manager filed an eviction case against him.[4] A process server said that he had left the summons and complaint outside Gelletich's door and mailed it to him, but Gelletich never received the summons.[5] Without knowledge of the court date, Gelletich failed to appear and thus lost his case by default.[6]

Gelletich is one of many who have been evicted from their homes as a result of a default judgment —that is, a judgment entered against a party, "without a full hearing before a judge," when they do not appear in court.[7] Eviction proceedings are meant to "ensure that the state does not sponsor wrongful deprivations of shelter."[8] However, this is not the case when "a plurality of all cases in landlord tenant court have resulted in defaults and most evictions have followed from default judgments."[9]

Rhode Island has made great strides in improving access to justice, specifically for self-represented litigants, and there are opportunities to continue these efforts, specifically in eviction proceedings where most tenants do not have representation. On average, twenty percent of eviction cases in Rhode Island end as a result of a default. In addition to the new resources for self-represented litigants on the Judiciary's website and the newly opened Judicial Resource Center located in the Noel Judicial Complex, Rhode Island is in the perfect position to continue innovating in ways that decrease default judgments and judgments on the merits in cases involving housing. Some solutions, adopted by other jurisdictions, include amending notice requirements, implementing court date reminder programs, and allowing tenants to miss one court date before being defaulted. Such reforms could lessen the court's reliance on the "drastic remedy"[10] that is default judgments and increase the number of decisions that are made based on the merits of the case.

The Eviction Crisis

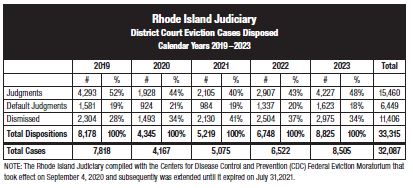

The threat of being brought to court for an eviction case is very real for renters in Rhode Island. Thirty-eight percent of households in Rhode Island rent.[11] Confronted with a tight rental market, many renters face housing insecurity: "[off the more than 32,000 lowest-income renters, 16,145 Rhode Island households are severely cost burdened, meaning they are spending more than half of their income on housing."[12] The effect of spending most of one's income is that even a small emergency can mean facing an eviction.[13] These problems, along with the end to the eviction prevention programs established during the pandemic, have led to a more than forty-three percent increase from 2022 to 2023 in monthly eviction filings for non-payment of rent.[14] In 2023, there were 8,505 total eviction cases in Rhode Island District Court.[15] This number, however, still hides one important aspect of the eviction crisis in Rhode Island—that is, the number of cases that resulted in default judgments.

The Role of Default Judgments in Eviction Cases

Default judgments are a standard part of the eviction process. Under current Rhode Island law, a landlord must send a tenant a demand letter for rent or a notice of non-compliance in order to proceed with an eviction case.[16] The next step is for the landlord to file a complaint in District Court and serve the tenant with the complaint and summons, which must include the date and time of the court proceeding.[17] The hearing date is set for fourteen to twenty-four days after the complaint is filed.[18] If a tenant does not appear in court for their proceeding, they may lose their case by default and be evicted.[19] The tenant then has only five days after the judgment is entered to file an appeal.[20] If they do not appeal, execution will be issued six days after the judgment is entered.[21]

Although there is growing recognition that default judgments contribute significantly to the eviction crisis and do not afford tenants any chance to assert legal defenses, the study of default judgments in eviction cases is limited.[22] This is, in part, due to a lack of data. One study, attempting to find default rates from jurisdictions across the country, noted that many jurisdictions do not collect default judgment data.[23] Of the existing data, that study found default rates ranging from approximately eight to fifty-five percent.[24] While the Rhode Island Judiciary does not publish default judgment data, the Rhode Island Judiciary supplied data for this article.[25] The chart below depicts the makeup of eviction cases in the Rhode Island District Court from 2019 to 2023. The rate of default judgments entered across these five years is fairly consistent; on average, default judgments were entered in 19.4%—nearly one-fifth—of all eviction cases.[26]

The Bar Journal assumes no responsibility for opinions, statements, and facts in any article, editorial, column, or book review, except to the extent that, by publication, the subject matter merits attention. Neither the opinions expressed in any article, editorial, column, or book review nor their content represent the official view of the Rhode Island Bar Association or the views of its members

Lack of Notice as Cause of Default Judgments

Currently, there are no studies on why tenants default in Rhode Island. Without such data, Rhode Island should look to studies conducted in other jurisdictions. A report prepared by the Massachusetts Law Reform Institute and the Justice Center for Southeast Massachusetts, as well as a report from the Shelter Center for Social Justice at Temple University Beasley School of Law on default judgments in Philadelphia, both found that a lack of notice of one's court date was a frequent cause of a tenant receiving a default judgment.[27] In Massachusetts, failure to receive a summons and complaint represented the most common reason cited for a tenant's failure to appear in court.[28] In Philadelphia, Tack of notice' along with 'lateness' was also the most common reason for a tenant's failure to appear.[29]

It's Not Too Late to Sign Up For Your 2025-2026 Bar Committees!

It's not too late to join a Bar Committee for the 2025-2026 Bar year! Committees offer valuable opportunities to stay engaged, connect with colleagues, and contribute to the legal profession.

With the Bar's new and improved website, the process to join or renew is faster and easier than ever. If you served on a committee during the 2024-2025 Bar year, you must renew your membership for 2025-2026 by logging in to the new site, going to your My Dashboard, and updating your selections. If you are joining for the first time, simply log in or create an account, go to your My Dashboard, and select the committees you would like to join.

Committees typically meet once a month from September through May, either virtually or in person. The time commitment is minimal, and getting involved is a great way to take the first step toward future leadership within the Bar.

There is still time to get involved; visit ribar.com to get started today!

These studies also highlighted concerns regarding specific methods of notice. In Philadelphia, about thirteen percent of the tenants in the study reported that they did not receive personal notice even though a process server had signed an affidavit that notice had been accomplished.[30] The report emphasized that "in the event of a dispute, there is no way to confirm the processserver's statement."[31] A similar number of tenants also reported that they did not receive the complaint that was said to have been posted 'conspicuously' on their premises.[32] The report explains that posting can be unreliable because "[t]he notice can be damaged, removed, or destroyed by weather."[33] Posting also creates challenges for tenants in multi-unit properties because there might be multiple entrances.[34] Mailed notice can similarly be unreliable; the study noted that "because the Court uses regular (not certified) mail, there is no way to verify that a mailed notice reached the tenant."[35] All three of these methods will fail if the tenant has abandoned the building because they believed they had to after receiving the...